The most intricate, well-developed, and interesting villains of all time are not really worth much if you never have engaging conflict with them. In fact, an amazing showdown can make up for a lot when it comes to villains. I could explore that concept in a lot of ways, but right now I’m going to explore how Paper Mario (and in many ways, any game using a similar “Action Command” combat system) encapsulates the concept of a villain that is actually fun to do battle with.

Before I go into my points, I’ll summarize how that combat system works for those unfamiliar. Essentially, it functions like ordinary turn-based rpg combat with one key difference: every action in the game has some kind of quick-time event associated with it, usually some kind of timing mini-game. The events are unique to each of your own moves, as well as your enemy’s moves, and succeeding at them increases or decreases the damage they deal, respectively. As an example, once you’ve selected a power strike with one character, you might have to hold and then let go of a button at the right time to get its maximum damage. Enemy attacks are generally blocked by pressing a button just before they strike you, mitigating or entirely negating their damage.

The enemies of Paper Mario are, from a purely narrative perspective, not interesting. These are basically the same Goombas and Koopas you’ve been stomping on for decades now, even the bosses are generally just more colorful variations on old standbys. And there was never any incredibly engaging backstory for Piranha Plants or anything. And as before, you have a fairly straightforward set of commands with which to deal with them. There are more than the original game (Hop, Don’t Hop, and Throw Fireball) but still. You and your party members each have about 4-5 meaningfully different actions you can take at any one time.

But where it gets interesting is in the depth that is still contained within this simplicity. With so few variables, your strategy is going to change a lot based on minor alterations in the enemy. Oh no, this Goomba has a pointy hat, now he deals extra damage and we can’t jump on him. But, unless we spend some special points to use a ranged attack, we won’t be able to hammer him until we get rid of the other Goombas in front of him. However, we might need those points for a later fight, so is it better to take some extra damage or spend some of our extra points? And how is your decision effected if you’re better at the minigame for executing the ranged attack than for blocking the Goomba’s spikey headbutt? It’s not exactly a mind-bending paradox, but that’s a good bit of strategy that comes into play just because a Goomba in the enemy’s back row has a hat on.

And that’s just one tiny possible variable. The game can give all sorts of twists and bonuses to the enemies you’ll be fighting (wings, life-draining attacks, defensive options, charge-up attacks) that give you a lot more to think about in any given fight than your average “hit the slimes with the swords until they fall down” random encounter in an rpg. Stacking multiple boosts on individual enemies and diversifying their groups forces you to approach them in different strategic ways and always be ready to develop new tactics for new opponents.

So, as you’re wandering around the Mushroom Hills or wherever, and you see some turtles coming at you, you don’t sigh as you reach for your hammer to take down another mob of featureless creatures. You can’t just throw your higher health and attack power and assume that, so long as you remember to make your warrior attack and your caster throw spells, you’re going to come out on top. The battles demand attention, and the enemies demand your respect. This makes them feel important, like they are meaningful obstacles in your quest, rather than some randomly generated mob of semi-diverse roadblocks waiting for your to annihilate them.

Each enemy encounter becomes something more like a puzzle, an assortment of interesting pieces that you can solve in different ways. To keep the bosses raised on a higher standard, each one has a gimmick completely unique to it that forces you to change how you might normally address it or make interesting decisions in your tactical approach. One boss takes less damage from hammer attacks, but multiple hammer attacks in a row can disable it for a turn. Another spawns additional enemies each time is attacked, and at the end of a round will consume any that you don’t defeat in order to regenerate its health.

Now, all of this is not a substitute for creating villains with amazing motivations, personalities, ect. But, the format of certain stories, particularly those told in rpgs, tend towards having a lot of villainous bosses that simply don’t get enough screen time to be well-developed. Robot tanks, giant spiders, workaday dragons, all make decently attractive foes but aren’t going to be incredibly interesting, as far as their character goes. However, you can make them very interesting mechanically, with a tactically diverse combat system and interesting innovations (or “gimmicks”). And obviously, the more engaged you are with a villain the more engaged you are with the hero’s quest to defeat them, with the narrative they are embroiled in, and with the consequences of the story.

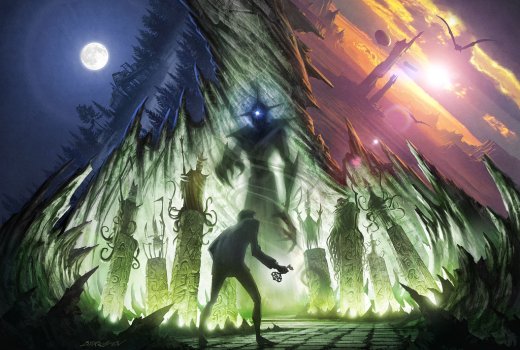

Even if the villain looks like this: